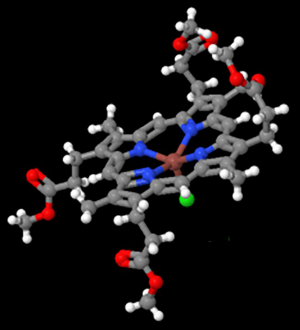

At the University of California, Berkeley, John joined the lab of Melvin Calvin, the 1961 Chemistry Nobel Laureate. Because of Calvin’s interest in photosynthesis, the lab was focused on porphyrins. Thus did John – likely the only physicist in a building full of chemists – dive into porphyrin research, through circular dichroism (CD).

John inherited the magnetic CD instrument of Calvin’s former Ph.D. student Edward A. Dratz. He rebuilt the machine a few times and eventually hooked it to a computer.

Among John’s achievements during this period was a theoretical paper that resolved discrepancies in magnetic CD measurements of porphyrins reported in the Ph.D. dissertations of Dratz and Michael M. Malley, a Ph.D. student at the University of California, San Diego.

“Malley and Dratz knew each other,” John recalls. “They exchanged compounds to make sure they were working on identical material. They ensured that their magnets were properly calibrated. And they got hugely different answers.” By postulating a certain condition, John could explain everything that the graduate students found.

At the University of California, Berkeley, John joined the lab of Melvin Calvin, the 1961 Chemistry Nobel Laureate. Because of Calvin’s interest in photosynthesis, the lab was focused on porphyrins. Thus did John – likely the only physicist in a building full of chemists – dive into porphyrin research, through circular dichroism (CD).

John inherited the magnetic CD instrument of Calvin’s former Ph.D. student Edward A. Dratz. He rebuilt the machine a few times and eventually hooked it to a computer.

It was the first instrument in Calvin’s lab that could send data directly to a computer.

Among John’s achievements during this period was a theoretical paper that resolved discrepancies in magnetic CD measurements of porphyrins reported in the Ph.D. dissertations of Dratz and Michael M. Malley, a Ph.D. student at the University of California, San Diego.

“Malley and Dratz knew each other,” John recalls. “They exchanged compounds to make sure they were working on identical material. They ensured that their magnets were properly calibrated. And they got hugely different answers.” By postulating a certain condition, John could explain everything that the graduate students found.