Why Do People Decide To Give Back to Their Alma Mater?

By John Clark Sutherland

Remarks at the April 21, 2016, celebration of the establishment of the Betsy Middleton and John Clark Sutherland Dean’s Chair in the College of Sciences

Why do people decide to support their alma mater? Perhaps because the short time we spend as undergraduates is frequently a pivotal period in life. Small decisions can lead to huge consequences. For me, it happened when I was a first-quarter senior, when I agreed to a blind date with Betsy Middleton.

Betsy was a first-quarter freshman at Emory University. I had a three-year head start, but she finished her undergraduate degree in three years and her doctoral studies in another three. I beat her to a Ph.D. by just three months!

My education was physics, physics, physics, but much of my scientific career involved biological physics, made possible because Betsy was a biologist – I had a live-in tutor. This evening, I am glad that two of Betsy’s cousins, Henri Brown and Terry Pelick, along with Terry’s husband, John, are able to be with us.

Because so much happens during our college years that influence the rest of our lives, it is natural that we would like to give something back. But the institution we attended no longer exists, except in our memories. We cannot pay back, but we can pay forward to benefit succeeding cohorts of students.

That got me thinking about what determines the value of a college degree. To me, the value proposition of a degree from a particular institution has two parts: the direct and the indirect components.

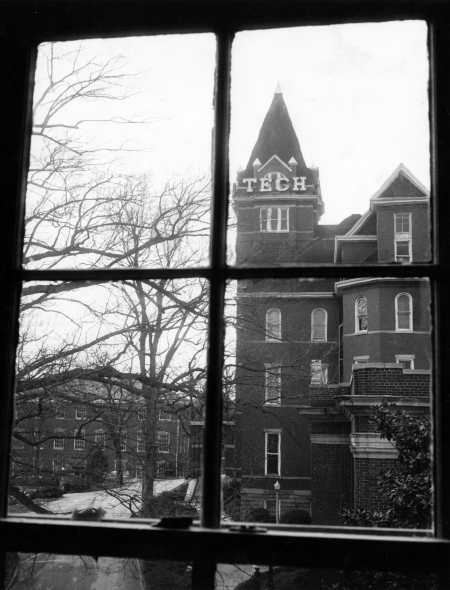

Tech Tower in the 1960s. Courtesy Georgia Tech.

From left: Paul Goldbart,

James Stevenson, John Sutherland. Courtesy Georgia Tech.

Because so much happens during our college years that influence the rest of our lives, it is natural that we would like to give something back. But the institution we attended no longer exists, except in our memories. We cannot pay back, but we can pay forward to benefit succeeding cohorts of students.

John Sutherland with family members. Courtesy Georgia Tech.

The direct component is what students learn, which is largely influenced by three factors: the particular student, the faculty members with whom they interact directly, and their immediate circle of students.

One of the most important factors for success is a strong work ethic. I was fortunate in this regard.

With us this evening are two of my nieces, Dee Wallace and Randall Watts; Randall’s husband, John; my nephew, Clark Johnson; and his wife, Deborah. They will agree with me that their grandfather, my father – a man who did not have a college degree, but rose to become the president and a director of a Fortune 500 company – was an excellent role model for a strong work ethic.

The second factor is the small number of faculty members that a student interacts with, at most about 40. A few of those interactions will be more important than the rest.

For me, Vernon Crawford, Joe Ford, and especially Jim Stevenson, all from the School of Physics, were especially important. I am so glad that Dr. Stevenson, accompanied by his daughter Jana, could be with us this evening.

Jim was my dissertation director, and he introduced me to vacuum ultraviolet spectroscopy, which played a major role in part of my career. Jim also taught the third-quarter introductory physics course that I took as a sophomore at Tech.

Jim’s labs were different from the usual, where you walk in, find some equipment and a protocol waiting, and then just follow the recipe. Instead, there was an empty laboratory table. We were given a goal of determining something. The questions were: What measurements do you need to make, and what equipment do you need to make them?

From that starting point, we had to determine our own protocols. It was more difficult than following a recipe – and more rewarding!

The final factor in the direct component is the small group of students that a student interacts with directly. This group helps set the tone of the instructional environment, but in special cases, other students can be very important.

In my case, Joyce Rice, later Nickelson, was such an individual. She was a math major, and there were not many women at Tech at that time. So I am delighted that we are joined by Joyce’s daughter, Dr.Joyce Ellen Nickelson; her husband, Dr. Reg Albritton; and one of Joyce Rice Nickelson’s great-grandsons, Sean Risoldi.

The value of a degree extends beyond what individual students learn. That’s the indirect part of the value proposition, which depends of the reputation of the institution. Interestingly, this part of the value of a degree can change after you graduate, hopefully for the better.

A couple of personal experiences illustrate the importance of this indirect component.

A year or so after moving to East Carolina University, where I served as chair of the Department of Physics, I was in the gym early one morning, wearing a Georgia Tech t-shirt – the one with an image of Tech Tower and the words “North Avenue Trade School” in large letters.

I encountered a professor of psychology who also occupied a leadership position at East Carolina. She knew that I was the chair of the Physics Department. We said hello.

As she read the lettering on my shirt, I could see the look of apprehension grow on her face.

“Where did you get that shirt?” she asked.

“Oh, this is from my alma mater,” I replied.

The apprehension turned to a look of dread.

“You…you…didn’t go to a trade school!”

“Well, actually, this is just a nickname we have for Georgia Tech.”

The angst turned to relief.

“That’s okay then,” she said. “One of my cousins is assistant chair of applied mathematics there.”

So, I guess I was saved by a family connection.

But the message was clear: Whatever your qualifications, it would not be good for the chair of the Physics Department to be the product of a trade school – except for the one on North Avenue.

Another experience demonstrating the value of Georgia Tech’s reputation occurred some years earlier.

I was chatting with a postdoctoral physicist during coffee hour in the lobby of the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory. He commented that his appointment would be ending soon and he had begun looking for a permanent position.

I mentioned that the physics department at Georgia Tech was looking for a couple of assistant professors, one of which was a solid-state experimentalist.

“Yes,” he said, “I saw that, but I don’t want to go to one of those high-pressure, research-intensive places.”

I was proud of myself for managing a soothing response. “Oh, I certainly understand,” I remarked and wished him luck.

But inside my head, it was “GO TECH!”

In my world, his characterization of Tech was a great compliment.

So Chairman Pablo Laguna, Dean Paul Goldbart, and Provost Rafael Bras, I thank you and your predecessors for having set the School of Physics, the College of Sciences, and the Georgia Institute of Technology on the path to becoming an outstanding institution with an international reputation for excellence in teaching and research.

And I encourage each of you and your respective successors to maintain this trajectory.

To me, the value proposition of a degree from a particular institution has two parts: the direct and the indirect components.

Whatever your qualifications, it would not be good for the chair of the Physics Department to be the product of a trade school – except for the one on North Avenue.

Tech Tower. Courtesy Georgia Tech.